The electronics industry has become a strategic sector with tremendous economic impact, but it is totally dependent on imports as of now. Despite blooming demand in the domestic market, India lags in manufacturing compared to other developed countries. How can this be resolved and what is the reason behind this? Let us find out.

Electronics is one of the fastest growing industries in the world. In spite of having excellent academic institutions teaching electronics, India lacks in manufacture of electronic goods. This leads to import of electronic components as well as most finished products.

As a country, we have heavily relied on China, the US, and some other countries for raw materials, technology, and intermediary goods. Though manufacture of some key electronic products and other necessary electrical equipment may not be possible soon, India can begin producing less sophisticated components—provided certain measures are taken.

Innovation drives self-reliance

Innovation does not take place overnight but needs a strong support system to drive it. We need an ecosystem to push and channelise our talent, nurture, and facilitate it. For that the right mindset and culture are important.

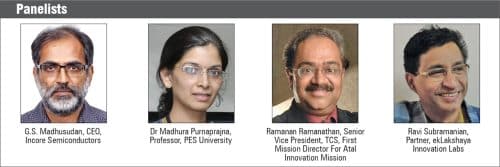

Dr Madhura Purnaprajna, Professor, PES University says, “We as a community are in need of leaders, people, researchers to drive this innovation. There is no dearth of talent, and the need is to facilitate innovation early while in the learning process.” According to her, innovation is a very tricky subject that has to be driven through careful thought, culture, and mindset. She adds, “I strongly believe that innovation is the key to drive self-reliance in the Indian scenario.”

From employment perspective, electronics industry is very significant, especially with the country’s demand being projected at $400 billion by 2025. The industry and academia need to come together as joint co-creators of innovation for self-reliance.

Experts believe this is right time for innovation in the electronics sector as compared to a decade ago. “We have platforms at the school level creating hobby electronics and getting people to actually do electronic development. In addition, these products are available so easily in the market that it’s quite easy for somebody to get in,” says Ravi Subramanian, Partner, ekLakshya Innovation Labs.

Collaborate and co-develop

Academia could play a larger role than merely being a supplier of manpower to the industries. Innovative results can be achieved through academic efforts. “Public and private collaborations are some directions to channelise these innovations,” says Purnaprajna.

From an academic perspective, the professor says, she has seen immense interest of the student community to participate in project-driven initiatives. She thinks it would be great to move away from rote learning towards a problem-solving environment. “Industry people could come in earlier, maybe have an overlap of one or two years and motivate candidates. We tend to give them a theoretical perspective, while industry experts can give them a practical problem. This is how you can build socially-relevant solutions.”

Purnaprajna suggests this could be a better way than industry experts arriving at the end of fourth year for recruitments. Industry partners can participate in co-developing curriculum and projects along with students and faculty members in the long term. As universities become more open to making changes in curriculum, experts believe industry participation can take innovation forward. With industry coming into the picture early a real big difference can be made possible.

In contrast, G.S. Madhusudan, Founder & CEO, Incore Semiconductors, says initiatives and programmes collapse in absence of institutional drive. “A bachelor’s course in electronics means the candidate should have at least got some experience in designing a practical SMPS, audio amplifier, CPU kit, and probably one more design either in digital or analogue.

These, when built practically, tie the theory and practice. So, even if the prototype does not succeed, it allows us to teach how to analyse what went wrong or right, which leads candidates to debug or figure out their wrongs and create success stories in future. This is engineering, where you go through the whole process of reasoning and analysis of building systems. So, there needs to be a difference in the approach and method of teaching.

At present, when a student transitions from university to industry, the initial months are unproductive. Madhusudan thinks there should be an apprenticeship programme for a year after the four-year academic study, in place of short-term internships. “Despite the fact that all kits are available as open source, there is a lack of guidance,” he says.

Going beyond research

For innovation, research is an absolute necessity. Our institutions already have an ecosystem that focuses on research. So, industry-academia collaboration could inject new scientific ideas into industry.

There are quite a few institutions that are keen on getting into product development. They could take it to the next level by supporting startups with some money based on their ideas. “We are very uniquely placed in terms of getting the next-level BB ecosystem, getting eased up as well as the government initiatives pushing us in terms of innovation in the electronics sector. There is a lot of opportunity for the students who look at developing prototypes, or as projects are done in colleges as part of the curriculum,” says Subramanian.

There arises a doubt whether full-blown products can be created in spite of opportunities everywhere. A lot of companies organise competitions to sponsor good ideas and convert them into useful products. The product or the prototype can be shoddy, but the process of engineering is what experts love to focus on.

Sadly, we do not have encouraging collaboration between the institutions and industries to share industry’s problems to research and find solutions. Ramanan Ramanathan, Senior Vice President, TCS and First Mission Director for Atal Innovation Mission, appreciates the efforts of Niti Aayog, some universities, and government initiatives that enable research and collective development. He suggests setting up of incubators by industries to provide opportunities and increase capabilities. Rather than just placement, industries should also encourage research activities.

Ramanathan points out the success of Atal Innovation Mission, which has seen overwhelming response from industry and universities. It has over 10,000 mentors to support budding engineering students. He says, “Setting up an incubation centre is a method of having industry and technology partners to attain a mentoring network. I think the government should also do its role in encouraging such interactions. However, the universities and industries have to practically play the role they want to participate in.

There has to be a very proactive approach and an awareness of the industry’s role in boosting and making India self-reliant and enabling the export of electronics.”

Boosting entrepreneurship

The industry-academia collaboration seems to be a two-way street. There are universities and colleges that have established incubation centres. Whereas in entrepreneurship, the journey does not happen in a day, but starts from the level of entrepreneurial thinking. It involves reading, listening, and calculating to develop the culture of entrepreneurship and innovation. There is a proactive marketing requirement by academia to the industry.

For instance, if there is a problem faced by an innovator in an MSME that does not have the bandwidth to help in solving it, it could approach an academia’s industry cell. They should pay small stipends to such academia. When done actively, this opens up a way to expose students to industry’s actual needs, which would help in building the future entrepreneurs.

India has more than 400 incubators and over 55,000 startups. The country has pushed its position from the 81st to the 48th place in just five years in the global innovation index.

Ramanathan considers infrastructure as the second pillar of self-reliance followed by technology demand. “By reducing the dependency on imports through greater emphasis on local manufacturing, design, electronic development, we can boost our exports. All we need to do is to empower the young students by creating an ecosystem of innovation, entrepreneurship, and the ability to do advanced research,” he says.

Madhusudan thinks the curriculum is too heavy with theory and that there is a serious need to have a significantly stronger practical focus. With not many lab exercises that are spread throughout the course, we need to revisit the practical curriculum, he opines.

Unfortunately, India has a cultural problem, where going into business is considered capitalism and has negative connotations in most parts of the country. It becomes easier to discourage entrepreneurship in such a scenario.

This article has been compiled by Abbinaya Kuzhanthaivel, an Assistant Editor at EFY, from a panel discussion held at Asia Innovation Summit 2021. The panelists in the discussion were Dr Madhura Purnaprajna, Professor, PES University; Ramanan Ramanathan, Senior Vice President, TCS, and First Mission Director For Atal Innovation Mission; Ravi Subramanian, Partner, ekLakshaya Innovation Labs; and G.S. Madhusudan, CEO, Incore Semiconductors